About a year ago I was finalizing an illustration of a very special fossil invertebrate that hadn’t yet been officially named or described. It is special for a number of reasons:

• The fossil is from the famous Burgess Shale formation in British Columbia, Canada, a World Heritage Site that’s remarkable because its fossils are from a period in Earth’s history when complex life was first evolving, and because the soft parts of the animals are preserved. That’s a relatively rare phenomenon in any fossil, let alone for ones as ancient as 506 million years old.

• The species is a worm with a crown of tentacles, its anatomy a unique combination of traits from two different modern groups of animals (the enteropneusts and the pterobranchs).

• It is classified as a hemichordate, a group of animals with an extremely sparse fossil record, so it’s discovery is important to our understanding of the evolution of this group.

• As a tribute to the person who inspired his interest in biology, Karma Nanglu ultimately named this fossil (in part) after his father.

• The opportunity to illustrate this fossil reminded me of a turning point in my life when I first became interested in paleontology and science illustration.

Shortly before I graduated from college,* my first-rate geology professor Murray Borrello recommended a book to me: Wonderful Life, by Stephen J. Gould. I read it that summer after graduation and was entranced by the story of early life on Earth (as told through Burgess Shale fossils) and I was enamored with Marianne Collins‘ delicate stippled illustrations of the diverse invertebrate fossils. That book and Marianne’s illustrations inspired me to pursue a career in science illustration.

When I entered graduate school for an MFA in science illustration, I was encouraged to choose a specialty; naturally I chose paleontology. I took classes in paleontology and invertebrate zoology to complement my art degree. However, my career path had a mind of its own; first I illustrated fishes, then all kinds of animals, some plants, a few anthropological projects, and lately I’ve been creating infographics and coin designs on a wide range of themes. Evidently a science illustrator doesn’t really need to specialize; I am happily a generalist. Even so, I always savor opportunities to illustrate my favorite subjects—fossil invertebrates—though these commissions are few and far between.

That’s why I was so thrilled last year to receive a message from Jean-Bernard Caron, the Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Royal Ontario Museum, asking if I’d be interested in doing a reconstruction of a fossil invertebrate. Not just any fossil invertebrate, however; this was a newly-discovered species from the Burgess Shale, the very formation discussed in Wonderful Life. Of course I was interested!

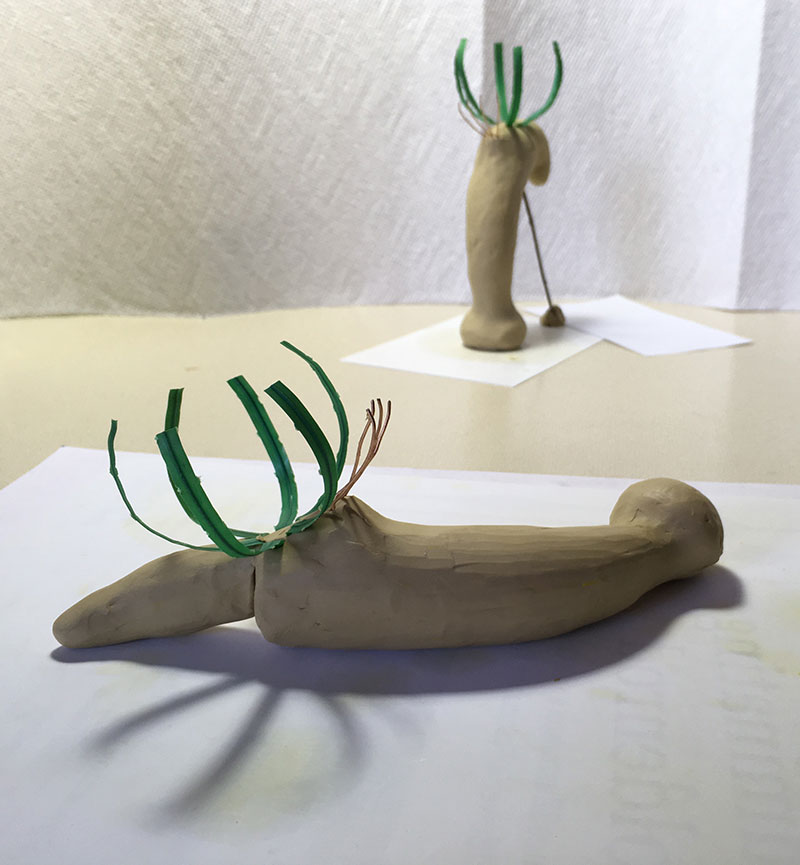

For this illustration, I worked closely with Dr. Karma Nanglu and Dr. Caron. As with any fossil species, there are no photos of the living animal to use as a reference for a drawing. I relied on the expertise of the paleontogists who had closely studied the fossils, and their recommendations to view images of living acorn worms, a related group of animals. I also sculpted crude representations with modelling clay, wires, and twist ties in order to better visualize the forms in perspective and under lights.

It is exciting to see that Dr. Nanglu’s and Dr. Caron’s research about the fossil, named Gyaltsenglossus senis**, is now published (here in Current Biology), along with my illustration. A third author, Dr. Christopher B. Cameron, also contributed to the paper. I’m so thrilled to have played a role in bringing this Burgess Shale animal to life. If you want to read more about this new fossil and its significance, as well as see photos of it, this press release and this article are great summaries that put the research into context.

*For my Bachelor of Fine Arts degree, I attended Alma College, a small college in the middle of Michigan. I’m forever grateful for the liberal arts education that required me to take classes in disciplines outside of my major of Studio Art. I signed up for a basic geology class to fulfill a science credit, and I loved it so much that I signed up for another. Murray Borrello’s exceptional teaching enhanced the appeal of the subject, and from this blog post it’s clear that the geology classes and their professor influenced my career.

**The etymology of Gyaltsenglossus senis: Gyaltsen, pronounced ‘‘GEN-zay,’’ (with a hard <g>) for Dr. Nanglu’s father, who inspired his interest in biology as a child, and glossus from the Greek glossa, meaning tongue—a common generic suffix for hemichordates. Senis is from Latin senex, meaning old.